In the last post, I explained the idea for my research – to look at the increasing use of assessed and online reflection in higher education. Not many people seemed to be talking about this particular combination of factors and how they might play out in practice. I really wanted to know how teachers and students were negotiating what I saw as a tricky dilemma: reflective writing is supposed to be authentic and personal, but assessment and being online pull it in other directions, towards an awareness of an audience and a fear of losing control.

In the last post, I explained the idea for my research – to look at the increasing use of assessed and online reflection in higher education. Not many people seemed to be talking about this particular combination of factors and how they might play out in practice. I really wanted to know how teachers and students were negotiating what I saw as a tricky dilemma: reflective writing is supposed to be authentic and personal, but assessment and being online pull it in other directions, towards an awareness of an audience and a fear of losing control.

To find out more, I interviewed 12 teachers and 20 students from across six higher education programmes in the UK. All had been involved in assessed (or what I’ve been calling “high-stakes”) online reflection for a year or more (1 teacher was no longer doing so, but all the rest of the interviewees were at the time of the interviews). A range of subject areas were included in the research, but all of them were professional or vocational in focus, which seems to match the way that online and assessed reflection is being adopted. Half the programmes were at undergraduate level, and half at postgraduate. Some were online, some campus-based, and one was a blended programme where students spent blocks of time on campus and other blocks interacting online.

I wasn’t sure what to expect from my interviews. Would any students or teachers describe a problem with high-stakes online reflection? If not, what would they say? If they did, how would they get past it in order to do what needed to be done? What strategies did they use to make sense of their practices?

Here are some examples of the kinds of questions I asked students and teachers in my interviews.

For students:

- How much did you write reflectively in your portfolio/blog? How often? What motivated you to write?

- Did you get as much feedback as you expected? Was it the right amount?

- While you were writing, how aware were you of the assessment criteria or of being assessed?

- Who is your audience for this portfolio/blog? How do you hope they will see you?

- Can you write personal things in your portfolio/blog? Have you? What happened/ would happen if you did?

- How is it to do this writing online?

- Who owns your portfolio/blog? Why?

- Have you edited the portfolio/blog at all? Would you?

- What do you think is going to happen to your portfolio/blog after this course?

For teachers:

- How are students on your course supported to be reflective?

- How do you understand your own role in terms of supporting or guiding reflection?

- Are there any problems for you with the notion of reflective writing?

- How ‘real’ or ‘authentic’ does your students’ reflection seem to you?

- Do students ever address you in their reflective writing (implicitly or explicitly)? What do you make of that? How do you respond?

- Do you think your students enjoy doing reflection?

- Has a student ever shared information in their reflections that you felt was too personal? How have you responded to this?

- What makes a good reflection? A bad one?

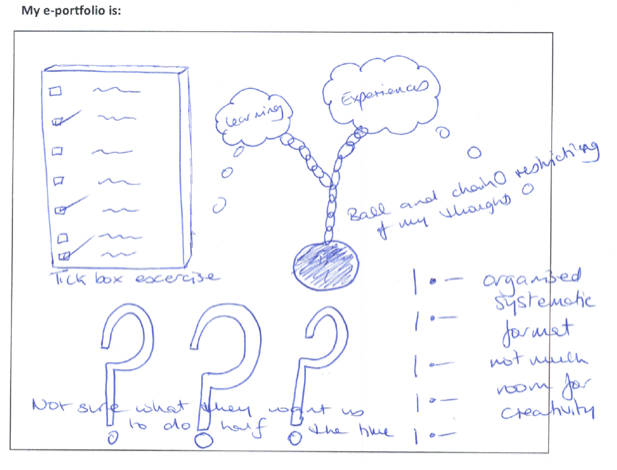

I also asked interviewees to describe or draw a metaphor for their e-portfolios or blogs. I got some really funny and insightful responses this way. Here’s one, where a student describes her e-portfolio as being like a “ball and chain restricting my thoughts”, and like a “tick box exercise”:

It turns out I was right to think there were some tensions around these practices. Different people experienced them differently. For example, some students very straightforwardly wanted to do what was required of them, but didn’t know how. Others understood what was expected, but felt constrained by those expectations. Some of their teachers felt uncomfortable about the possibility that they exercised power over their students through assessing reflection, but at the same time believed that they could help their students be empowered through reflection.

Many students worried about what to say, and what not to say, in their online reflections. Some teachers worried about that, too, and wondered what consequences online disclosure might have for students down the road. They tried to address this by doing things like policing students’ reflections, or producing very structured templates for students to fill in. Both teachers and students sometimes imagined they weren’t actually doing things “on the web”, in order to feel safer.

Some teachers saw reflection as a way of ensuring that students were “fit for practice” in their chosen profession, and welcomed more visibility of students’ learning processes. But students often struggled to produce the sorts of reflective writing that their teachers wanted, which was often very different from other kinds of writing they’d had to do before.

In short, there was a lot going on, and a lot that wasn’t really being discussed or even necessarily acknowledged. It seemed to me that certain kinds of practices and concerns were being “masked” or disguised by the way that high-stakes online reflection was being understood and explained to students.

In the next post, I’ll talk about the way that I ended up using the metaphor of the mask – which I’ve been talking about for a few years now – to structure the PhD.