So, I said I would write some blog posts about my phd research – what it was about, what I did, and what conclusions I’ve drawn from it. This is the first one of those. It explains what provoked me to do this research. I’ll follow it up with explanations about the questions I was trying to answer, the arguments I made, and what I’ve learned and concluded – that will be for future posts.

The idea for the research came back in 2005/06 because I wanted to understand more about a practice that seemed to be increasingly common in higher education courses in the UK at least: assessing online reflection. There’s still not a lot of evidence that shows exactly how widespread this is, but some research that the Centre for Recording Achievement in the UK has done over the past few years indicates that it is a fairly common practice, especially in professional programmes (like teaching, medicine, social work and law).

If you’re wondering what ‘reflection’ means in this context, so was I. A fairly standard definition of reflection is that it’s a way of deliberately looking back at things you’ve experienced, done or thought in the past to understand and know yourself better. Writing reflections down might also allow you to capture and review how you change over time. Different people say that the point of this self-knowledge is: to become more authentic; to be more aware of how you’ve been shaped by external influences; to be more flexible and able to develop yourself; to become a better professional; to make your learning more personal; to learn more effectively.

So, why assess reflection? One explanation is that students won’t willingly engage in anything that doesn’t ‘count’ in assessment terms. The argument is that they need the motivation of marks in order to make them do this thing – reflection – that is good for them. Giving something a mark also shows that teachers value it, and that’s important, especially as university education gets more time-pressured for both teachers and students.

But what effect does assessment of reflection have? Questions have been debated in a few academic articles about the relationship between self-development and external requirements, about how to prevent students from censoring themselves or trying to write to please their assessors, and about how something as individual as reflection might be assessed fairly. The most interesting questions for me were: aren’t there really profound tensions between assessment and the concept of self-motivated, personal, authentic reflection? How do teachers and students negotiate those tensions, and what does reflection become in those circumstances?

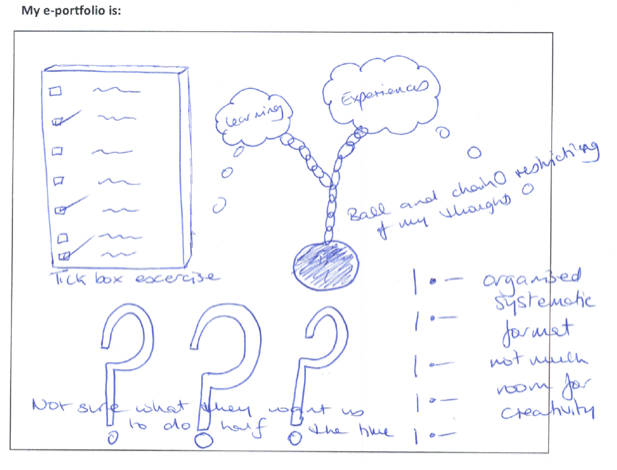

What about doing reflection online – what were the issues there? When I started my research, online environments, like e-portfolios, were being talked about a lot as a wonderful development in helping students record their development through reflection and also through storage of ‘evidence’ of learning and achievement. These environments were often visually attractive, offered a lot of support and structure, and they were trendy and digital. Doing reflection online could also solve practical problems like storage of and access to reflections.

Some people were concerned about the effect of having reflection stored on the web – they were worried about surveillance, about privacy, and about accidental disclosure of things that were confidential or too personal. So online reflection as a concept seemed to involve a delicate balance between disclosure (which is the whole point of reflection) and caution and control (which you need because the web is ‘dangerous’). In attempting to deal with these new concerns, some of the earlier unanswered questions about assessment and reflection seem to have been abandoned.

I wanted to know: what happens when you throw all of this stuff together – reflection, assessment, and the web? That’s what my phd research was about.

If you’re interested reading more about some of this, I suggest these references:

Ayala, J. (2006). Electronic portfolios for whom? Educause Quarterly, 29(1). Retrieved: 21 July 2011. http://www.educause.edu/apps/eq/eqm06/eqm0613.asp?bhcp=1

Boud, D. (2001). Using journal writing to enhance reflective practice. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 2001(90), pp. 9-18.

Creme, P. (2005). Should student learning journals be assessed? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 30(3), pp. 287–296.

Kimball, M. (2005). Database e-portfolio systems: A critical appraisal. Computers and Composition, 22(4), pp. 434-458.

Strivens, J., Baume, D., Grant, S., Owen, C., Ward, R., & Nicol, D. (2009). The role of e-portfolios in formative and summative assessment: Report of the JISC-funded study. Wigan: Centre for Recording Achievement. Retrieved: 26 July 2011. http://www.jisc.ac.uk/whatwedo/programmes/elearningcapital/studyontheroleofeportfolios.aspx

Strivens, J., & Ward, R. (2010). An overview of the development of Personal Development Planning (PDP) and e-Portfolio practice in UK higher education. Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education, Special Edition: Researching and Evaluating Personal Development Planning and e-Portfolio Practice, pp. 1-23. Retrieved: 26 July 2011. http://www.aldinhe.ac.uk/ojs/index.php?journal=jldhe&page=article&op=view&path[]=114